Rhythm Revolution in the Southern Seas

Li Jinhui and His Musical Tour to Southeast Asia, 1928-1929

Xiangjun Feng

PhD candidate, UC Berkeley

In May 1928, Li Jinhui 黎錦暉 (1891-1967), who is now remembered as the father of modern Chinese popular music, embarked on a performance tour with his China Musical Troupe 中華歌舞團 to “Nanyang” 南洋, or the Southeast Asian ports and cities constituting the nodes of the Chinese diaspora. Starting from Hong Kong, they toured Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Batavia (Jakarta), and nineteen other cities in the British and Dutch colonies. Notwithstanding an acrimonious falling out in February 1929, the tour was a huge success in its time, and it bears great significance in many regards for our retrospective understanding of the global character of modern Chinese popular music.

Existing scholarship on this tour remains sparse and sketchy, mainly because of the lack of historical records, except for Li Jihui’s autobiography and some troupe members’ memoirs, which are brief, one-sided, and might have been tailored to the particular pressures of the post-1949 political atmosphere. This paper excavates multifaceted primary sources that have never been used before in order to establish the first comprehensive account of this tour. In addition to reconstructing unknown historical details, special attention will be given to records found in the local periodicals published by both Chinese immigrants and the European colonizers, revealing how the Southeast Asian locals received and reacted to the new rhythms from China. The tour was not only a success among the Chinese immigrants, but also a great shock to the colonizers’ stereotypical understandings of what the “Chinese” sounded like.

By contrast to domestic reports and the persistent memory that Li Jinhui was the protagonist of the tour, in fact the troupe was often perceived as representing the cinema industry. In the spotlight and epitomizing the public image of a modern new rhythm was Li Jinhui’s daughter Li Minghui 黎明暉 (known by the locals as May May Lee), who was already a famous film star before joining the troupe. This misperception urges us to rethink the particular mediality of modern Chinese popular music in the global context: music was not “modernized” as an enclosed domain following a national and teleological agenda; instead, it was an integral part of the emerging media culture that was by nature fluid and global.

Carrying the Sounds of the Chinese Jazz Age Abroad:

Jasmine Chen, Golden Age Chinese Pop Music, and Crazy Rich Asians

Andrew Field

Prof. of History, Duke Kunshan University, China.

In this paper, I focus on the story of one Chinese singer and her extraordinary career as a jazz singer and interpreter of “golden age” (1930s-40s) Chinese pop music, in an effort to trace the global flows of Chinese pop music and its connections to both the legacy of 1930s Shanghai and the Chinese diaspora. This paper will highlight issues of Chinese identity, particularly in the Asia Pacific region, and it will also use the example of Jasmine Chen’s career to examine how Chinese musicians and singers are perceived and received by various audiences abroad.

Jasmine Chen began her musical career as a classical pianist. After earning a Master’s in Music at Leeds College in England in 2003, where she was first introduced to jazz, she made her way from her native place of Liaoning to Shanghai, where she built a career as a jazz singer in the city’s thriving jazz scene. She has since traveled to many countries around the world to perform in concerts, clubs, and festivals. Her body of work encompasses many different traditions and regional styles of jazz music, yet she is known in particular for her modern interpretations of jazzy pop songs from 1930s-40s Shanghai, such as the classic song “Ye Lai Xiang,” which was first performed by the Manchurian film star Li Xianglan (Yamaguchi Yoshiko) in the 1940s. Her work as a jazz singer came to the attention of the producers of the Hollywood hit film Crazy Rich Asians (2018) and she appears in the film and on the soundtrack for the film singing Chinese “golden era” pop tunes. The paper will also discuss this film and connect the film’s story of the “crazy rich Asians” of contemporary Singapore back to the musical and cultural legacy of 1930s Shanghai, through the vehicle of Jasmine’s performance in the film.

Echolocation: Listening to the (Chinese) Cold War in Jamaica

Andrew F. Jones

Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures,

University of California, Berkeley

With the rise of Michael Manley's democratic socialism in 1970s Jamaica, the Caribbean island became a hotly contested micro-front of the global Cold War. These years also brought the white-hot efflorescence of a politically engaged, socially conscious, and sonically innovative Afro-Jamaican music, reggae. What does it signify, then, that much of this music was produced by a cohort of Hakka Chinese entrepreneurs, record producers, and studio musicians? As is increasingly acknowledged, Chinese-Jamaican producers like Leslie Kong at Beverlys Records, Clive Chin of Randys Records, Herman Chin-Loy at Aquarius, and Jo-Jo Hoo-Kim at Channel One contributed to almost every new development in midcentury Jamaican popular music, from ska to rocksteady to reggae, and on to the vastly influential studio-mediated form known as dub music.

As members of an ethnically marginal Hakka migrant community, these participants in the Jamaican music industry were concerned not only with the proximate "tribal warfare" (often subsidized by the CIA) between rival political parties in the streets of west Kingston, but also with a far more distant Cold War conflict between the Republic of China and revolutionary "Red China." In this paper, I will trace how these events were refracted in Jamaican music, listening for the ways in which Afro-Jamaicans located themselves with respect to an imagined Chinese revolution.

I will go on to explore how Chinese-Jamaican producers and their musical collaborators developed reggae, and especially its echo and reverb-laden sound, as a kind of navigational tool, locating their island home within the currents of imperial history, diasporic movements of labor and capital, and the geopolitical fractures of the Cold War. The paper will focus in particular on several of the most influential "riddims" (instrumental tracks) in the history of Jamaican music, Baba Brooks' "Shank I Sheck" (1964), the Revolutionaries' "Kunta Kinte Dub" (1972), and Barry Brown's "Far East."

How New Chinese Music Conquered Western Ears

Frank Kouwenhoven

CHIME Foundation, Leiden, The Netherlands

In the late 1980s, socialist China suddenly found itself at the heart of the international avant-garde music circuit. Young composers discovered Western avant-garde and quickly caught up with it. They began to write new pieces combining traditional Chinese and contemporary Western sounds, and surprised audiences with their fresh, original and provocative works. Before long, a number of these artists began to earn international fame, and they were even hailed as ‘Chinese Beethovens’. This paper examines the evaluation of new Chinese sounds abroad, and traces the earliest stepping stones in the dissemination of Chinese new music beyond national borders, namely

1) An exodus of young Chinese composers who went to study (primarily) in Europe and with Chou Wen-chung in the USA in the early 1980s.

2) Early Western premiere performances of a number of Chinese orchestral works, notably Ye Xiaogang’s Xi Jiang Yue at the Asian Pacific Festival in Wellington in 1984, and Guo Wenjing’s Suspended Ancient Coffins on the Cliffs in Sichuan in Berkeley, California, the same year.

3) Major festivals of Chinese New Music held in Hong Kong in 1986 and 1988 (ISCM), with numerous premiere performances.

4) A festival of new Chinese music organized by Mike Newman in Edinburgh in 1987.

5) Tan Dun ‘rescuing’ the Gaudeamus Festival in Amsterdam 1989 with his performance of On Taoism.

6) A series of Chinese concerts organized by the Dutch Nieuw Ensemble and conductor Ed Spanjaard from 1991 onwards.

More important than a summing-up of events is the question how the Chinese new pieces played were received by the first Western listeners. Newspaper reviews indicate that these works overwhelmed Western ears with their ample references to Chinese traditional sounds – then utterly unknown outside China: the rowdy folk songs of Chinese farmers, the deep humming and bell ringing of Buddhist worshippers, the battering on gongs and drums of village bands, and the intricate rhythms hidden beneath the deafening surface of that music, the special vocal colours of southern dialects, the vocal acrobatics of Sichuan opera, and more.

Intriguingly, such traditional sounds have hardly found their way to Western stages directly since. It is mainly when they are incorporated in new compositions and integrated with French, German or American avant-garde techniques that the flavours of Chinese opera and rural ritual music achieve a major impact on international concert stages. What, if anything, does this say about the way Western listeners perceive new Chinese music, and Chinese music more generally? The author has organized numerous concerts of Chinese traditional and new music in the West. He bases his conclusions on newspaper reports, extensive interviews with Chinese composers, and his own experiences with programming contemporary and traditional Chinese music in Western concert halls.

Making Waves in Oceania: Resistance, Traveling, and Musicking

Yuan-yu Kuan

Lecturer, Music and Asian Studies,

University of Hawaii at Manoa.

The paper explores non-governmental encounters between Aboriginal Taiwan (AT) and the greater Pacific, and thereby provides a much-needed perspective on the present circulation of largely unnoticed Greater China-related sounds abroad. Specifically, I investigate the ways AT musicians link civic engagement with indigenous rights and land ownership directly to Hawaiʻi’s current Mauna a Wākea Thirty Meter Telescope Protests. I examine two cases:

1) An AT musician, Ado Kaliting Pacidal, who participated in the Hawaiian movement and released an album, Sasela’an or Breath, that documents her inter-island journeys, including songs that are collaborations with Austronesian musicians from Aotearoa (New Zealand), Madagascar, Rupa Nui, Solomon Islands, and Tonga; and

2) AT musicians who recorded “Kū Haʻaheo” and shared it on social media. Using the notion of musicking as “way-finding,” I discuss two musical journeys: 1) making music while physically traveling and 2) making music as metaphorical travel between musical cultures.

These cases show the musicians’ resolve to circumvent governmental interference by initiating direct dialogue with another indigenous nation. I argue that musicking as traveling interweaves an open-ended history for indigenous peoples of the Pacific, generating waves of decolonizing forces that reach both distant and not-so-distant Pacific shores.

“Singing to Whom?” Sonic Articulations of Hong Kong

Frederick Lau

Director, Center for Chinese Studies

Chair and Professor of Ethnomusicology

Chinese University of Hong Kong

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

The reputation of Hong Kong has attracted intense global attention in recent years, starting with its role as a leading international financial hub to the ending of British colonial status, the 2014 Umbrella movement, and the 2019 protests sparked by the now-defunct Extradition Bill. While these images capture the ethos and historical moments of Hong Kong as a Chinese space, there is no one way to read Hong Kong as it traverses through different phases of its political and modernist journey. This conundrum lies precisely on the flickering identity of the place and its people and how it shapes people’s imagination of self and their future.

This presentation focuses on Hong Kong’s sonic expressions of the last several decades to provide multiples snapshots of Hong Kong history. I explore Hong Kong musical genres such as “spirit music” “Cantopop,” and recent Protest music to identify the sentiment and politics that belies each genre and era. By privileging issues of agency, subjectivity, meaning, and power of the music, I want to anchor Hong Kong’s historical fluidity in the technology of musical exchange, musical styles, aurality, and creation as added dimensions to the study of China and its history.

On the dilemma of Chinese rock musicians’ outreach toward the global

Chang Liu

Manchuria, Beijing, Musical Entrepreneur, Germany

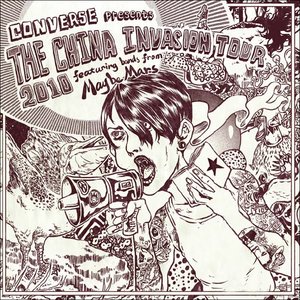

“And since then, I no longer listen to Chinese rock”, Wang Yue (王悦) – the vocalist of China’s first all-female punk band Hang on the Box – says in a documentary. By “since then”, Wang refers to when she discovered dakou cassettes, and this reference makes Wang a member of China’s dakou generation. Focusing on musicians from China’s dakou generation, this paper will argue, their outreach toward the global is triggered by the arrival of dakou cassettes and the sudden exposure to a great amount of western rock music in front of which a newly emerged authenticity discourse makes them believe rock music from abroad is more authentic, and thus urges them to reach out to the global. The materials I use here are my first hand experiences from full-time working in Beijing’s music scene between 2007 and 2011, and I will primarily focus on the bands associated with Wudaokou’s (五道口) live music venue D22 and Maybe Mars Records (兵马司唱片). The venue and the label were both owned by Michael Pettis – professor of finance at the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University. Using Pettis’ connections in the US, the label initiated a series of exchanges and collaborations with international musicians (Sonic Youth, etc.), producers (Wharton Tiers, Martin Atkins, etc.), and brands (Convers, etc.), and thus pushed its bands to the global stage. Through the sponsorship of Convers, Maybe Mars Records organized the “China Invasion Tour” for its bands in the US. Yet, these musicians’ longing for authenticity backfired. I will conclude by considering how Chinese musicians from the older generation developed a counter discourse to discredit the younger musicians as copycats.

Whose Classical Music? Chinese Musicians and the World

Barbara Mittler

Prof./Chair, Chinese Studies, University of Heidelberg,

Director of the Heidelberg Centre for Transcultural Studies

A recent novel by French author Etienne Barilier entitled Piano chinois (Chinese Piano) features two French music critics debating the performance of a Chinese pianist (clearly, the avatar of Yuja Wang) who plays a concert of Scarlatti, Brahms and Chopin. While one of them declares her the “greatest pianist of all days,” the other denounces her play as “lacking in spirit,” calling it “artificial and imitative.” Their “blog exchange” offers important reflections on the question of universality in art and culture more generally and—more specifically—the meaning of musicmaking in a transcultural context: why does this music, the emblematic product “of the West” play such an important role “in the East”? Does Europe “lose its soul” or can it actually find it again on the “Chinese piano”? In this discussion, I consider debates over “authenticity” and “creativity” in Chinese music which champion essentialisms about China’s loss of her “own” musical traditions and “Chineseness” as well as China’s inability to fully grasp those musical traditions “originating” with “others.” The paper will question why, in this rhetoric, even the best Chinese musicians “must still depend on Western mentors,” why classical music would be considered the “least Chinese, and most explicitly Western of all art forms” and why, “in spite of the enormous outward success of China’s music students,” people should continue to have doubts that “the spirit of ‘Western Classical Music’ has sunk deep roots into China’s society.“

The paper argues, that classical music has become the new face as well as a new phase of Chinese music-making. To practice classical music has become a stand-in for cultivation, a significant sign of an individual’s cultural capital, a critical element to effective self-fashioning in China. To successfully practice a classical instrument can gain a Chinese teenager entrance to one of the key high schools even without a perfect score and accordingly, the practice of classical music is much more common especially among the younger generation in China than anywhere else in the world (which is why Lang Lang is now organizing special music schools for kids in the US and Europe who are not as well provided with as their Chinese counterparts).

Crazy Rich Asians: Chinese-language Songs, Hybrid Pathways, and Acts of Erasure

Marc L. Moskowitz

Prof., Department of Anthropology, University of South Carolina

Music is created by sound but also by minor spaces, or the absence of sound. In turn, a good story is often marked by what is not said as much as by what is. A pregnant pause might indicate discomfort without having to state it. The omission of a fact might lead a detective to the culprit or the hero to discover that his best friend was the villain all along. As with any film, and its accompanying soundtrack, what is left out helps to support the story that is being told on an intuitive level. To some degree it also tells a more complex story than the original work. It is quite possible, in fact, that this kind of messaging is so subtle as to be unintended by the creators but once it has come into being that is irrelevant. The meanings are there, nonetheless.

The film Crazy Rich Asians (J. Chu 2018) met with a stunning degree of success that, if we are to be honest, probably had more to do with audiences who were starved for Hollywood representations of Asian-Americans than the quality of the plot or the dialogue. The soundtrack, however, is an inspired a compellation of East and West hybrid production. This includes homages to the Shanghai Jazz Era of the early 1920s and 1930s, Hong Kong classics from the 1950s and 1960s, contemporary PRC rap, as well as new Chinese-language renditions of American songs ranging from Motown to the works of Elvis Presley, Madonna, and Coldplay. This mixing and matching of Chinese and American musical elements create a visual and sonic hybridity that highlights the lives of both Singaporean and Chinese-American characters who negotiate the crossroads of Chinese tradition and global youth cultures where they are often rendered both invisible and silent. For those who were not familiar with Chinese-language music, it serves as an introduction, a taster box of sorts, to a century of Chinese-language musical genres and creations. Audiences that are already familiar with the region, participate in a celebratory review of the rich varied forms that Chinese-language popular music has to offer.

Yet it should also be noted that there is a certain tunnel vision at work in the plot, the visual narrative, and in its sonic production. Critiques of the political economy are conspicuously absent. Taiwan’s central contribution to the last fifty years of Chinese-language music is also a noticeable lacunae in the soundtrack, which is hard not to read as a conscious preemptive surrender to the whims of PRC censorship. Singapore’s minority populations are absent both as characters in the film and as performers in the soundtrack. In this dreamscape, Singapore is transformed into a borderless and timeless China rather than being shown to be a distinct multi-ethnic culture whose citizens are as much a part of a diasporic community as the Chinese-American characters are. In short, the film and its soundtrack’s acts of erasure, and the story that those absences tell regarding “Chinese” music and culture, are at least as significant as what it does introduce to its audiences.

Chinese Music in a Changing Japan:

The Sounds and Meanings of Minshingaku, 1870s to 1930s

Edgar W. Pope

Prof., Aichi Prefectural University (Japan)

During the 1870s and 1880s, when Western music was being introduced to Japan but was still virtually unknown to most people, and many types of Japanese traditional music were being denounced as impediments to “civilization,” a genre of Chinese music known as minshingaku spread from its base in Nagasaki and flourished throughout the country. The gekkin, the most popular instrument of this genre, was widely played by both amateur and professional musicians, and its distinct timbre became familiar through public and private performances. Minshingaku melodies were disseminated through a Chinese-derived notation system and later through Western notation as well, eventually coming to be performed on Western as well as Chinese instruments. While minshingaku continued to be recognized as Chinese, its sonic influence was gradually being absorbed into the changing mix of Japanese music culture along with newly arrived Western music elements.

This process changed abruptly with the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894. A wave of contempt and even hostility toward Chinese culture caused the sounds of minshingaku to be driven out of the public sphere or separated from their associations with China. The genre never recovered its former status. In the 1920s, however, media technologies and rising exotic interest in China created a new cultural space in which the melodies and timbres of minshingaku could re-emerge as China-signifiers. These sounds were then mobilized through the media of records and radio to serve both the growing music industry and the interests of full-scale imperialism in the 1930s.

Chinese Sound Waves on Cuban Shores:

Chinese Music's Maiden Voyage to the Americas

Edwin Porras

PhD candidate, UCLA

The earliest mass migration of Chinese people to the Americas was recorded in Cuba, in 1847. Hoodwinked into signing eight-year labor contracts, coolies (i.e., Chinese indenture workers) were trafficked primarily from agricultural cities in the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong Province to fulfill the burgeoning labor demand of the sugar industry in Cuba. It is estimated that by 1867 there were approximately 20,000 Chinese in Havana, alone. Propelled by the arrival of Chinese merchants via secondary migration from Mexico and New Orleans, the Chinese diaspora experienced tremendous prosperity that transformed the barrio chino (est. 1870) into the largest most thriving Chinatown in the Americas and the Caribbean. This period of economic bonanza encouraged a series of high level-investments including the financing of the first Chinese theater in 1873. This paper is based on archival and fieldwork findings I conducted in Cuba between 2017 and 2018. First, I unpack the convoluted history of this Chinese saga and briefly explore the relation of the Chinese diaspora to their host country. Second, I survey the history and impact of Chinese culture in Cuba. I focus on two traditions, Cantonese opera and lion dancing, exploring their development, influence, and contribution to Cuban music culture. I finish my presentation by reporting on the present state of the Chinese-Cuban community as they struggle to preserve, transmit, and ensure their music culture's longevity.

Opera in Cantonese Sojourner Communities from Shanghai to San Francisco:

Modern Mobility of the Transpacific Network of Opera in early 20th Century

Nancy Rao

Prof. of Music, Rutgers University, New Jersey

In 1922, opera circles in Shanghai witnessed the historical meeting of Cantonese opera superstar actress Li Xuefang and Peking opera superstar actor Mei Lanfang. This much anticipated event signaled an important moment both in the rising significance of Cantonese opera in this cosmopolitan city, and in the development of modern mobility associated with Cantonese opera in the Transpacific network of the 20th century.

Aside from other social and economic forces, the newer modes of audio/visual/print media played an important role as well. Examining the social context and social actors involved in this historical juncture, as well as the activities of Cantonese opera performance in Shanghai, this paper will pursue an understanding of the notion of Cantonese sojourner community, and the significant role of Cantonese opera for such sojourner communities.

A significant part of the paper will consider Shanghai’s connection to and influence on another Cantonese sojourner community across the Pacific in San Francisco and the impact its performances had on foreign audiences and their perception of China.

Flying Sounds, Grounded Knowledge: Pigeon Whistles in Germany and the UK

Odila Schröder

PhD candidate, University of Nottingham

Pigeon whistles have long captured the imagination of people both in and outside of China. And though not exclusive to China, the instrument has become tied to its history in the Inner City of Beijing. Today, a small but strongly connected global community keeps practising the art of flying pigeon whistles.

Drawing on museum collections, texts portraying the practice produced throughout the late 19th and 20th century, as well as interviews with contemporary pigeon whistle enthusiasts based in Germany and the UK, I examine how knowledge about the sound and its origins has been kept alive until today – and how it has transformed throughout its travels. Rather than reproducing nostalgic imaginations of old or exotic sounds, I use pigeon whistles as a heuristic device to test the theoretical boundaries of “China sounds abroad”. While musical instruments might be one of the most traditional types of material culture associated with sound, I argue that the particularities of pigeon whistles allow us to rethink a sounds’ connection to space, discrepancies between performance and recording, authorship, and the embodiment of the extensive knowledge and training required to produce particular sounds. Exploring such issues in regard to sounds with such a long history of migration, reintegration, and historical imagination, I hope to provide a fruitful testing ground for the theoretical questions posed in this workshop.

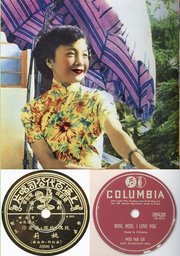

Travel and Pleasure of a Sonic Souvenir: “Rose, Rose I love You” (1940)

and the on-going Legacy of China’s First International Hit-Song

Andreas Steen

Prof., Department of Global Studies

Aarhus University

In the tumultuous and chaotic years of the Sino-Japanese war (1937-45), composer Chen Gexin, living in the modern extraterritorial treaty port Shanghai, wrote the love song “Rose Rose I love you” (Meigui meigui wo ai ni). In 1940, the 17-years young singer Yao Li recorded the song with British EMI-China in Shanghai. The song quickly became popular and while it was banned from public broadcasting together with the whole genre of the so-called ‘songs of the times’ after the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, it began to circulate abroad.

By the early 1950s cover versions appeared in the USA as well as in Great Britain, later also in Japan, Malaysia and Vietnam. During the 1980s, and amidst a wave of nostalgia, the song returned to Mainland China. Today, it has been re-recorded in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and is cherished as one of Old Shanghai’s most iconic tunes.

The paper explores the fate of the song and its composer, both of which were inextricably linked, and investigates the circumstances and different historical periods of this unusual cultural transfer. Meanwhile, the song has become a sonic souvenir and signifier, inviting us to reflect on the ownership and internationalization of melody and sound as well as on the impact of cultural politics on context, meaning and the pleasures of musical consumption.

Chinese Buddhist Soundscapes Abroad:

The Case of Foguangshan Humanistic Buddhism

in South African and Brazil

Hwee-San TAN

Associate Lecturer, Goldsmiths, University of London

Buddhism has always been an ambulatory religion. It spread from India to East Asia where Mahayana Buddhism strongly influenced by Chinese culture has developed into one of the three main Buddhist traditions.[1] In turn, during the 20th century, it gradually became widely disseminated in the West through Chinese migration and transnational movements. Today, Chinese Buddhism, in particular from Taiwan, is making headway in proselytising in the West. Taiwan’s Foguangshan Monastery founded by the monk Hsing Yun is one such example, with over a hundred branch temples spread from the northern to southern hemisphere.

Entrenched in Buddhist rituals, Chinese Buddhist chants are very much a part of the sonic landscape of Mahayana Buddhism. Within the monastic tradition, Chinese Buddhist chants are commonly conceived as having two forms of delivery: chang (to sing) and nian (to recite). The chang form comprise musically-sung hymnody, whilst sutra texts consisting of the Buddha’s teachings are recited. Texts of both these forms are steep in the Chinese written characters and language, whilst Buddhist rituals formulated have gradually been influenced by Confucian and Daoist ideas as well as Chinese socio-cultural practices. My paper will use the example of Nan Hua Temple, South Africa and Templo Zu Lai in São Paulo, Brazil, both of which are Foguangshan Monastery’s overseas branch temples, to consider if and how the sounds of traditional Buddhist music and religious practices are effective as a proselytising tool. I will also examine what strategies are used to overcome the barriers of different languages and socio-cultural contexts, and what meanings the religion and its sonic and ritual practices hold for the local communities.

My findings are in large part based on my indepth research in Taiwan on Foguangshan monastery from the 1990s. However, for my research on the two branch temples, I am using online research and social media spaces to collect data. This will give further scope to reflect and address the strategies for research across multiple sites and how they could be situated and framed.

Music, Nation, and Youth Activism: The European Sojourn of Wang Guangqi

Christina Till

Max Weber Foundation in Beijing

From 1920 until his death in 1936, the Chinese musicologist, student activist, and journalist Wang Guangqi (1892-1936) lived in Germany. Before his departure to Europe, Wang founded the influential Young China Association (Shaonian Zhongguo Xuehui) and edited the association’s journal Young China (Shaonian Zhongguo). In the journal, Wang proclaimed the reorganization of society by the association members, which would eventually lead to the rejuvenation of the Chinese people. During his sojourn in Europe, he extensively studied various models of youth organization as well as the role of culture in the construction of the modern European nation states. While abroad, he propagated a return to the essence of Chinese national culture, which he determined to be Chinese rites and music, would rejuvenate and save what he perceived as a “Chinese nation.”

By delineating Wang’s understanding of national education and culture, this paper will explain the transformation of his writings, from articles on socialism and youth activism to the propagation of a national music culture as distinct and exceptional features of a rejuvenated China. The paper will also take into consideration his experiences of living and studying in the Weimar Republic and, after 1933, in Nazi Germany as well as influences from his close network of likeminded Chinese intellectuals and former students in Europe. It will argue that Wang, revered today for his fundamental contributions to the field of musicology in China, saw the propagation and study of music in China as a project that predominantly benefited the creation of a common national identity.

The Chinese Empire Travels West:

Euphony and Cacophony of the 1904 World’s Fair

Di Wang

PhD candidate, Washington University

China’s debut at America’s first world’s fair in 1876 was unremarkable. A contemporary observer critiques that China’s contributions at the time “are chiefly from the coast…The vast interior of the empire… remains unrepresented.” The impression would change dramatically in 1904, when the Qing Emperor and Empress Dowager accepted President McKinley’s official invitation to take part in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri. The 1904 World’s Fair offers a rich archive for understanding modern China’s many sojourns in the industrialized West and their forgotten, consequential history. Aside from the triumphant zeitgeist encapsulated in Chang Yow Tong’s celebrated eulogy “China’s Message to Columbia,” the fair attracted diverse expressions of Chinese modernity that were largely drowned out by a public show of commitment, by both Manchu and American regimes, to a version of progress that was monolingual (English) at best, superficially euphonious at worst.

This paper recovers the divergent interests and investments at all levels of Chinese society that led to the summit. The triumphant moment of 1904 traced the evolution of Chinese modernity to America’s heartland, where its cacophonous, multivocal, polyglot expressions converged: The Manchu court seized the chance to forge diplomatic ties with the US; Chinese merchant-gentries residing at the treaty ports swarmed to the fair for commercial opportunities; the introduction of Chinese laborers injected a pernicious dose of anti-Asian racism in the American interior; Chinese Americans courted the Manchu prince in the fair delegation to support their political agenda to install constitutional monarchy, whereas the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen repudiated the highly anticipated Manchu presence in America and used the opportunity to consolidate his own base. These entwined voices (and silence) of 1904 World’s Fair are vital to the formulation of Chinese modernity, anticipating the tumultuous decade leading up to the 1911 revolution.

Playing with the Former Suzerain:

Chinese Resoundings in Korean Popular Songs from the Transpacific Jazz Age

Yamauchi Fumitaka

Prof., Graduate Institute of Musicology (in the College of Liberal Arts)

National Taiwan University

In the 1930s, when the relationship between China and Japan had rapidly worsened due to the latter’s aggressive military actions, certain types of sounds and musics that were intended to be perceived generically as “Chinese” by the listening public widely circulated across the territories of the Japanese empire. Promoted in Japanese as manshū merodii (“Manchurian melodies”) and later tairiku merodii (“continental melodies”), they resounded particularly loud after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

In this paper I will examine the case of colonial Korea in which such auditory China-signifiers took distinctive routes at a time when the production of Korean popular songs reached its first peak. Typically, their producers integrated Chinese-sounding words, musical phrases and instrumental tones and/or set the narratives in China. An analytical focus is given to these sonic representations and narrativizations circulated on Korean gramophone records.

This specific theme will be explored against a broader context of East Asian and transpacific history in which Korea was situated among the three imperial formations that came in competition for cultural hegemony in twentieth-century East Asia: China, Japan, and the U.S. I will consider, in particular, how modern Korea’s sonic de-Sinicization resulted from the repulsion of its former suzerain and its so-called civilization, how it became entangled with its Japanese counterpart, which was sought to construct an autonomous auditory sphere region-wide but only in the face of the alluring presence of American popular music, and how these de-Sinicization projects led to the commodification of Chinese resoundings under the specific conditions of capitalist modernity in colonial Korea.