Introduction

In this paper, I focus my attention on teachers’ lived experience in the time of Covid-19. Specifically, the study I am presenting explores the emotional impact the abrupt shift to online teaching had on teachers’ work and life throughout the various phases of the lockdown. I develop my argument by analysing teachers’ everyday work, using a qualitative approach, and constructing a small-scale empirical study. The study involved 13 teachers from different disciplines in secondary school (with students aged from 13 to 18). The research group, stemming from an in-service teachers’ educational course I conducted, was selected based on teachers’ interest and willingness to share and discuss their feelings and emotions. The study is based on a combination of in-depth interviews, dialogues and email conversations. Methodologically, my attempt is located in an emerging research horizon combining educational philosophy with empirical research (Feinberg, 2006; Mejia, 2008; Santoro, 2015; Shuffelton, 2015; d’Agnese, 2016; Hansen, 2017). However, in order to expose and justify my approach, a brief clarification about the way I conducted the research, and its background is needed.

Throughout my experiences as teachers’ educator, I have often encountered groups of teachers who passionately deal with their profession. Often, these teachers, given their deep commitment, were radically exposed to difficulties, frustrations, and failures, as well as, more than others, they could deeply feel the joy, passion and possibilities stemming from being-in-education. During the discussions staged in the courses I conducted, these teachers would often share insightful considerations and revealing feelings about several aspects of teaching, ranging from teachers-students’ relationships, curriculum, professional judgment, and side effects of passion and commitment. I would always take note of their interventions, and sometimes, at the end of the course, given the quality of interactions, I would stage research settings with the aim of systematically gathering such insights. However, at times, when comparing gatherings from experimental settings with the rough material emerged during the courses, I felt that something went lost. In those occasions, I was left with a subtle sadness and desire to recover the lost insights.

Of course, I cannot exclude that such a difference was due to a lack on my part to create an adequate experimental setting. However, I do believe that something more was at stake. Simply put, the matter teachers shared throughout the open time of discussions was something too slippery to reproduce in a dry experimental setting; the urgency they felt to communicate their deep feelings and insights was part of the matter they were sharing, and something hardly replicable on demand. Simply put, deep insights and emerging feelings are not at our disposal; if we wish to shed a light on the lived, bodily educational experience, we must carefully listen when and where such experience arises.

So, this time I decided to proceed in a different manner: I would have collected teachers’ witnesses, and insights in the instant they were produced, reserving myself the opportunity to deepen the most interesting aspects in the way and time teachers would have preferred: email, interviews via Google meet, WhatsApp messages and conversations. Of course, I informed the teachers from the very beginning about my research purposes and experimental setting. So, when something revealing was coming up to the surface, I invited the teacher involved to deepen her experience, focusing on her sensations and feelings, while exploring the possibility to further deepen her insights. Sometimes I also asked the teachers about an image or metaphor which should better convey the sense of the experience being shared.

Right from the outset, it was clear that difficulties, discomfort, and even suffering were important figures of teachers’ emotional state. Helplessness, dread, a “permanent sense of warning”, a “loss of oneself”—as two teachers described their emotions—were the prevalent mood of the online teaching experience. However, discomfort, anxiety and even angst were not the only feelings experienced by teachers I met. Along with these feelings—and, admittedly, to my surprise—some teachers also spoke about an “entirety”, a “fulfillment never experienced in their profession”, and even about “a deep sense of joy” and an “unknown freedom” in encountering their classes online. So, how should one make sense of such a diversity of emotions? Of course, one might argue that this question makes little sense, in that diversity of sensations simply relies on the diversity of persons and approaches—and, in a basic sense, this is true. One might even argue that teachers experiencing fear and angst when going online were simply unable to teach, for teaching also involves facing unexpected situations. However, it is my contention that much more was going on in teachers’ emotional horizon and lived experience. When listening to teachers, attempting to understand and unravel their emotions, I felt a common root: all those diverse and even opposite feelings were connected to a deep ethical engagement with students and profession, and the struggle to face an unknown situation in an unknown way. Otherwise stated, it was the entanglement between the unknown space in which teachers were thrown and their commitment and responsiveness to students that caused such a deep and diverse bunch of emotions. It is my hope that unraveling the common terrain where teachers were thrown, the feelings involved and the way they found—or not found—to deal with the new situation may help us to shed light on some aspects of teaching.

Philosophically, my attempt is phenomenologically developed, and is framed by Arendt’s and Heidegger’s thought. More specifically, I will analyse the cases drawing from three questions: a) Heideggerian understanding of “praesens” as the condition upon which the continuity between past, present and future arises (Heidegger, 1982/1927, 306-312); b) the variations of fear Heidegger points out in Being and Time and his analysis of angst (Heidegger, 1996/1927, 131-136; 173-178; c) Arendt’s thematization of action, beginning and the “startling unexpectedness” of living (Arendt, 1998/1958; 1977/1961).

The paper is organized in two parts. In the first one, I attempt to make sense of teachers’ sensations of discomfort and anguish through Heidegger’s thought. In the second section, I analyze feelings of joy and fulfilment via Arendt. In this section, I also give a hint about what the consequences of teachers’ gesture are for the formation of the educational community. I begin with the question of praesens, fear and angst as understood by Heidegger.

Praesens, fear and angst

In this section, I attempt to make sense of teachers’ sensations and feelings through Heidegger’s thought. The section is phrased into three steps: in the first one, I report some significant excerpts of teachers’ conversations and interviews; in the second step, I analyze praesens as the condition upon which “enpresencing” and the continuity between past, present and future may be understood (Heidegger, 1982/1927, 306-312); in the third step, I connect teachers’ witnesses with Heideggerian analysis of fear and angst (Heidegger, 1996/1927, 131-136; 173-178). I begin with teachers’ interviews.

Teachers’ interviews[1]

Silvia’s report[2]

“During the lockdown, I woke up with a weight on the chest, and a sense of permanent warning … I reached my computer, went online, and began the lesson. Sometimes it was not that bad. I could see their faces and I could imagine what was going on their mind… But there always was a gap I couldn’t fill. It was something like a permanent lack I was unable to compensate, and I felt guilty for that, although I knew it was not my fault. But this awareness didn’t help me make sense of my work.”

Luigi’s report[3]

“The Third B [Luigi’s class, ed.] had always been a hard class. But online it was even worse. When you see them and can interact face to face, you can draw their attention, make examples, use irony, or effectively reproach. When you are on Meet none of these things make any sense. Any reproach becomes comical… In two weeks, I find myself in a spiral… It was a total nightmare. Sometimes I was so panicked that I had to break up my lesson. I felt like I was going crazy… I had to call my wife just to speak with her and break that sense of anguish.” When asked about an image conveying such a sense of angst, Luigi reported about “an empty room, all dark, with my voice banging around… A total collapse.”

Gennaro’s report[4]

“When going online my prevailing feeling was that the class didn’t follow me… I was speaking in front of that screen with no evidence that someone would listen… I feel the right word for my experience is fear… It’s difficult to explain, but I felt the whole situation as an actual threat, and I couldn’t do anything to stop it ... At times, I couldn’t think, for if I did, I would have been paralyzed, in panic. I would just go on with my lesson trying to not think.”

Praesens

In Chapter One, Part Two of The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, when explaining the “temporal interpretation of being as being handy”, Heidegger introduces the question of praesens as the “horizonal schema of the ecstasis of enpresenting” (1982/1927, 303). As other basic Heideggerian questions—e.g., Temporality, existence, aletheia—the meaning and function of praesens is not so easy to capture—and in fact Heidegger, at the end of his analysis, states that praesens is “non-conceptually understandable.” (ibid., 309)

However, Heidegger furnishes a first indication of the meaning and function of praesens when stating that praesens is the condition upon which “presence and absence” present themselves to us (ibid., 304). Praesens is both the condition of possibility of the “beyond itself” (ibid., 304) and the condition of the possibility of the present, of the now. Moreover: praesens “as horizon” is the condition of “that which determines the whither of the ‘beyond itself’ as such” (ibid., 306). Even enpresencing, in Heidegger’s words, “understands itself as such upon praesens. […] Everything that is encountered in the enpresenting is understood as a presencing entity […] on the basis of praesens.” (ibid., 307). Praesens, then, is the very texture upon which world and things—emotions including —may be encountered, and the condition of the possibility of any understanding.

Based on this understanding, when analysing the statements from teachers I met, we may note that their words bear witness to a deep modification of the structure of praesens, of the horizon in which the very perception of students, themselves and teaching arise. Otherwise stated, any word, silence, gesture or act, any omission stands on the basis of such a modification. Even one’s commitment and projecting come to be felt upon such a different horizon, by means of which “anything like existent commerce with entities handy and extant becomes possible” (ibid., 309). This is also due to the relationship between praesens and temporality: given that Heidegger states that praesens is “already unveiled in the self-projection of temporality” (ibid., 309, emphasis added), such a deep structure goes hand in hand with temporality itself. The way in which temporality is given to teachers—or, in a Heideggerian vein, the way in which temporality temporalizes itself in teaching—relies on praesens, too.

Then, what happens to such a fundamental structure when one is “paralyzed, in panic” and cannot think at all? (Gennaro’s report) What if one is “so panicked… to break up” the lesson (Luigi’s report)? What if teachers in distress were to experience, using Luigi’s powerful words, “a total collapse of time”? In such a condition one is unable to think and act—to say nothing of projecting. Relationships are blocked, felt as threatening. The totality of gestures and emotions teachers feel and enact is under the shadow of such a curtain. Hoping, listening, projecting, awaiting, looking at, hanging back, inciting, caring, namely, the whole patrimony of comportments teachers enact in daily classroom activity is, as it were, swallowed by this unknown and disquieting kind of praesens; what Heidegger calls the “intentional comportments toward the futural” (1992/1928, 204) undergo the sway of this new texture of time-space, which, as I wish to display further, is permeated with feelings of alarm, fear and angst.

Teachers’ witnesses through Heidegger

Thus far, I have attempted to unravel the meaning of praesens as related to teachers’ words. In this second step, I respond to the question as to which modification of praesens teachers experience during pandemic. In a sense, I attempt to put to work Heideggerian analysis by connecting it to teachers’ words. My hope is that by filling Heidegger’s powerful phenomenological insights with the flesh and blood of teachers’ experience, we may shed a light on some deep aspects of teaching.

First to develop my analysis, two brief clarifications are needed. One of the strengths of Heidegger’s analysis of fear and angst is the exceptional rigor with which he describes the way these feelings inhabit and seize human beings. Heidegger’s description of fear, alarm, terror and angst as different states is exemplary in displaying how phenomenological analysis speaks from and to our body. However, it is exactly such a difference that is, at the same time, necessary and too rigid when compared with the modulations and the bustle of emotions experienced by teachers I met. Gennaro’s, Silvia’s, and Luigi’s words bear witness to a mess of feelings in which the distinction between, say, fear, alarm and panic is more a matter of nominalism than a means for understanding and penetrating their condition and emotional magma. The second clarification concerns the use of alarm, fear and angst as contiguous states—I take angst as also a modulation of fear. I understand that in Heidegger’s analysis angst is definitely distinguished from fear. Angst is a “fundamental kind of attunement” (1982/1927, 171), and in Heideggerian analysis it deserves to be treated differently. Since my paper is not concerned with Heideggerian phenomenology per se, I cannot delve into the argument, but it is clear enough that while Heidegger understands fear as a “mode of attunment” (ibid., 131), angst is framed as the “eminent disclosedness of Dasein” (ibid., 172). Moreover: in being implied in the fundamental questions of “being-toward-death” and “resoluteness”, we could say that angst is the door to the core of Being and Time. In my analysis, I will partially depart from this difference, for I will discuss angst as best suited to understand both teachers’ lived experience and important features of teaching. That said, let us begin with Heidegger’s phenomenological analysis. I will quote two passages from Being and Time describing fear and angst, and then provide my comment.

“The phenomenon of fear can be considered in three aspects. We shall analyze what we are afraid of, fearing, and why we are afraid […]. That before which we are afraid, the ‘fearsome,’ is always something encountered within the world, either with the kind of being of something at hand or something objectively present or Mitda-sein […]. What is feared has the character of being threatening. Here several points must be considered.

1. What is encountered has the relevant nature of harmfulness. […]

2. [H]armfulness […] comes from a definite region. […]

4. As it approaches, harmfulness radiates and thus has the character of threatening.” (ibid., 133)

About forty pages further, in Chapter VI, Heidegger describes angst as “[t]he fundamental attunement” and the “[e]minent disclosedness of Da-sein”:

“That about which one has Angst is being-in-the-world as such […] What Angst is about is not an innerworldly being. […] The threat does not have the character of a definite detrimentality which concerns that is threatened with a definite regard to a particular factical potentiality for being. What Angst is about is completely indefinite […]. The totality of relevance discovered within the world of things at hand and objectively present is completely without importance. It collapses. […] The fact that what is threatening is nowhere characterizes what Angst is about […] But nowhere does not mean nothing […]. It is so near that it is oppressive and stifles one’s breath—and yet it is nowhere […]. In Angst, the things at hand in the surrounding world sink away, and so do innerworldly beings in general.” (ibid., 176)

When comparing Heideggerian analysis with teachers’ experience, we note that teachers’ words and emotional texture bear witness to both fear and angst. Gennaro, Silvia and Luigi encountered the fearsome within the world, in a definite context, and it is also true that such an “harmfulness radiates and thus has the character of threatening.” What is problematic in defining their experience as just one of fear is that harmfulness, rather than aiming “at a definite range of what can be affected by it”, extends to the whole professional and even personal experience. Even their sense of self when being-in-education was jeopardized by a deep change. Then, while Gennaro, Silvia and Luigi encountered fear in the realm of “innerworldly beings”, they clearly experienced a sinking away of the world: Gennaro’s inability to think, his paralysis and panic, bear witness to the fact that being-in-teaching as such was the source of his angst. What Gennaro experienced while being-on-line was a total breakdown of intelligibility; in his experience the ecstatic projection of Dasein felt down. Otherwise stated, both acting and thinking collapsed, and the world itself pulled back. And yet, such an angst, comes—as fear—from a well-defined region: being-on-line with his students.

Similarly, Silvia speaks of “a sense of permanent warning”. Such a sensation, as I understand it, is a kind of mix between alarm, as the precursor of fear, and something very similar to the “nowhere” and “nothing” of angst. It is an indefinite yet stinging sense of danger, which looms over at any time. In this case too, what Silvia experienced is a collapse of the former praesens and the irruption of a new kind of praesens—as Heidegger writes, we cannot lose praesens, for praesens, simply put, is what enables the possibility of experiencing something. (1982/1927, 310) When teaching online, Silvia felt severed from both students and her profession. Even the bodily sensations Silvia experienced were akin to those provoked by angst: the “weight on the chest” she felt when getting up is akin to the angst’s feeling described by Heidegger, one which “stifles one’s breath”. And yet, in this case too, the threatening comes from a well-defined region and activity.

However, amongst the experiences reported, the one which better displays the features of angst was that of Luigi. He spoke about a “total collapse”, a sense of panic which forced him to break the lesson and call his wife. Even the image he found “an empty room, all dark, with [his] voice banging around” is a powerful representation of such a pervasive yet unphatomable feeling. And yet, in this case too, Heidegger’s description is at the very same time, apt and partial. When speaking of angst Heidegger states that “[w]hat Angst is about is completely indefinite” and “[a]ngst does not know what it is about which it is anxious.” (1996/1927, 176) However, this was not the totality of Luigi’s experience. Luigi did know where angst came from, and he could exactly locate the source of his angst; and yet such a root—being-on-line-with-students—provoked a sinking away of the world or, in Heideggerian terms, of the “innerworldly beings in general” (ibid., 176). Luigi was not oppressed by this or that problem of teaching: Luigi was oppressed by the possibility of teaching as such. That which was threatening approached Luigi from a well-defined region—and yet, as Heidegger states, it also was “nowhere”.

It is important to note that Luigi was forced to move on with a lesson which not just didn’t make any sense: he was forced to move on with a lesson which put such a loss of meaning in his body, pushing him to a limit possibility, namely, the death of his project. By drawing from Heidegger’s analysis of death, we could say that Luigi was experiencing “the possibility of an impossibility” (ibid., 330). His project, namely teaching, was impossible to pursue in the situation he found himself in, and yet the project was there, hideously disfigured, and it was throwing him in angst. By drawing from Thomson’s acute interpretation of Heidegger, Luigi was experiencing “a global collapse of […his] identity-defining life project”. However, what rendered Luigi’s experience so peculiar was that Luigi was experiencing the collapse of any projecting without being freed by projecting itself; he was experiencing a collapse of praesens, of the connection with temporality and wordly horizons, without the possibility of being released by the praesens of teaching. Otherwise stated, Luigi, in being a committed teacher, passionately chose the praesens and projecting that he has to endure. While human beings are thrown in “the possibility of an impossibility” which death is Luigi, in being committed to his students, was the author of his own “possibility of impossibility”.

Freedom, joy and fulfilment

Thus far, I have attempted to make sense of teachers’ experiences of fear and angst through Heidegger’s thought. In this section, I analyze a different range of emotions emerging from online teaching, namely, feelings of “entirety”, “fulfillment” and “joy”. I shall make my point by drawing from Arendt’s questions of action, beginning and “startling unexpectedness”. The section, as the first one, is phrased into three steps, respectively committed to a) reporting significant excerpts from teachers’ interviews; b) analyzing Arendtian questions of action, beginning and “startling unexpectedness”; and c) analyzing teachers’ emotional experience while sketching out the building of the educational community. I begin with teachers’ interviews.

Teachers’ interviews

Davide’s report[5]

“During the lockdown, I had to leave my study room to my son; thus, I worked in my bedroom. At the beginning it was awkward: in the background you could see the bed and clothes lying all over the room… I managed to put a background from Google tools, but for some reason it didn’t always work. After a while, I resolved to accept the situation, and began to joke about my mess… I began to feel a kind of coziness in that situation. I mean, not just my own coziness in being in my bedroom with a cup of coffee… I felt a kind of shared, common coziness… everyone in her bedroom or living room, with her cup of coffee, chocolate, juice or whatever… So, we decided to have coffee-break together. Some students would prepare toasts, others would even cook… It was strange, for we were separated, far from each other, and yet we were closer than ever. At some point I thought it would have been nice playing some music in the background when teaching. Classical music, rock, pop… we all felt a kind of togetherness in that strange situation… New connections began to emerge… I mean, connections among topics, among students, between me and them, between them and such new topics… At last, I felt students speaking with their voice. I mean, they began reading poetry, making personal comments writers… Everything was new in those months.”

Giovanna’s report[6]

“At the beginning it was bewildering… before the screen, speaking to everyone as ever, but in a very different way… You couldn’t know whether your students understood the topics… it was even difficult to understand whether they were there to listen. In some way, it was embarrassing. So, as a way out, I began to concentrate on the topic being explained.” When asked about her focus, Giovanna said: “I intentionally decided to exclude any thought about whether students were there and what they understood about the lesson. I began to delve into my topic. Should I find an image, I felt as a researcher at a microscope...” At this point I asked if one could label her lesson as a kind of study. Giovanna told, “yes, I was studying, but I was studying in front of my class!” When asked about the outcomes of her gesture, Giovanna said: “Unexpectedly, students were interested in such a strange lesson… They were following me… They began to interact and delve into the topics… I discovered a new way to teach… I experienced an unknown freedom by teaching online, from my bedroom.”

Action, beginning and “startling unexpectedness”

The questions of action, beginning and the “startling unexpectedness” (Arendt, 1998/1958; 1977/1961) are central to the understanding of Arendtian oeuvre. They are not just extensively treated by Arendt throughout her career; they are also the core from which many cherished questions unfold. Through them, questions of humanity, natality, existence, connect and illuminate one another in a web of significances that enriches the meaning of these themes, thus presenting an open and powerful conception of life. However, with my end in view, far from presenting a full-developed account of these themes, in this step I will present some features which may help shed a light on the excerpts I selected.

In The Human Condition, when discussing the common ground upon which action and speech should be understood and their “unique distinctness” within the wide range of “activit[ies] in the vita activa,” (1998/1958, 176) Arendt states that “action reveal[s] [human beings’] unique distinctness.” Through action, human beings “distinguish themselves instead of being merely distinct”. Action is the way “in which human beings appear to each other, not indeed as physical objects, but qua men. This appearance, as distinguished from mere bodily existence, rests on initiative, but it is an initiative from which no human being can refrain and still be human.” (ibid., 176-177).

Through this statement, Arendt overturns the meaning of action, with far-reaching educational consequences. For Arendt, by means of action, newness and human beings come into the world as such. In the Arendtian account, in fact, action takes place “between men,” and only through action may human beings’ “specific, objective, worldly interests” arise. These interests, in Arendt’s words, “constitute, in the word’s most literal significance, something which inter-est, which lies between people and therefore can relate and bind them together.” (ibid., 182) Then, for Arendt action is strictly related to the possibility human beings have to take upon themselves the responsibility, burden, and bearings of their distinctness. Without denying the well-known Arendtian concern about any attempt to find the essence “of human existence,” (ibid., 9) we may infer that, in Arendtian terms, action is essential for being human and that to take “initiative” is, for Arendt, something that characterizes human beings as such: by means of action, human beings come into the world accomplishing the newness to which they are destined. How and when such an initiative should be taken and enacted is left open and undetermined by Arendt. However, to enact ourselves on our own initiative is what makes us human. As Birmingham aptly noted, in Arendt action is grounded in the “archaic and unpredictable event of natality.” (2006, 3)

We should also note that for Arendt being human and being a beginner who performs her own beginning through action in a public space are one and the same thing. This is because the significance of action is twofold. First, action is central to understand and act freedom. As Arendt states, human beings “are free […] as long as they act, neither before nor after; for to be free and to act are the same” (Arendt, 1998/1958, 153); second, because action is essential to addressing and producing the new, and education reflects exactly such a broad and persistent commitment to newness. Through their capacity to act, human beings fulfill the promise contained in their birth: “The new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting.” (ibid., 9) Women and men are free because they are “a beginning” (ibid., 167).

At this point, I wish to highlight that the accomplishment of newness, its “character of startling unexpectedness” (ibid., 177-178), is not something added to human beings, something we as humans may or may not accomplish. As humans, we come into the world as “initium, newcomers and beginners” (ibid., 177). As Arendt states in The Crisis in Education acting “for the sake of what is new and revolutionary” (Arendt, 1977/1961, 189) for “the infinitely improbable which actually constitutes the very texture of everything we call real” (ibid., 170) is the first aim of education.

Such an understanding comes to reframe the interpretation and construction of one’s identity. Here, we should bear in mind that in Arendt the public and political space precedes and grounds individuality: according to Arendt, the subject reveals itself through its actions and speech, activities one may pursue only when one is connected to other human beings in the public arena. Then, it is not just that we cannot know in advance how our actions will be taken and understood by others, but rather that, more radically, through action one discloses oneself to oneself. That is to say, one comes to know who one is when acting and speaking, not before. Human beings thus come to know who they are through their ongoing engagement with others, in endless and ever-changing processes, whose structure and aims come to the fore in concrete situations of life.

According to Arendt, then, we may conceive of the educational space as one in which human life takes form in all of its features, not just as places where one acquires knowledge and competencies in order to face and manage the world. This is so for living is established in the dimension of togetherness. Failure to recognize such a public dimension of meaningfulness results in “modern world alienation,” that is, the “flight from […] the world into the self.” (Arendt, 1998/1958, 6) To clarify, the central point in Arendt’s understanding is that the uniqueness of human beings emerges by them revealing to others who they are through their actions and speech while, at the very same time, revealing to themselves who they are. Therefore, we cannot know who we are before such a revelation occurs. The dimension of educational community is thus the root from which both one’s being and becoming can grow, changing in unpredictable ways, accomplishing the “miracle” of natality.

Teachers’ witnesses through Arendt

At this point, we may put the question as to what kind of teaching and educational community emerge from Giovanna’s and Davide’s words. A first thing worth noting is that the lockdown interrupted the space-time of normal schooling, producing the conditions by which a different space-time was able to emerge. Such a different space-time, with everyone in one’s room with one’s belongings and private things, rather than creating a sense of distance and dispersion, created a new intimacy and nearness, in which private and public were not just mixed: private and public were unrecognizable in their own features, and, in a sense, their very split was useless for understanding the context, because a new environment emerged. As Davide effectively said, “everything was new”. In such new environment connections themselves were caught in a new web of meanings which transcended them, thus building a new community.

Such a newness also is a defining feature of Giovanna’s teaching. Albeit Giovanna’s response to embarrassment and discomfort was quite different from that of Davide, the arrival point was similar. The intentional neglect of students she enacted, rather than resulting in a kind of solipsistic teaching, resulted in a new, engaging teaching. Students were more involved than ever; from an exclusion of the community and even of communication, came out a the discovery of a new behavior towards topics being studied. Giovanna, in a sense, was teaching in a gap. So, which kind of terrain may come out from a gap, and which kind of meaning may be built and found, given that when teaching we are always-already in the presence of some meaning? In order to set up a tentative answer, I wish to focus on the pronouns used by Giovanna in her report. At the beginning of the interview, while openly speaking about the intentional decision to exclude any thought about the students, she reported: “I began to concentrate… I began to understand… I began to delve”. It is as if she had to exclude students in order to teach at all. At the end of her interview she stated, with a smile of surprise, “we discovered a new way to teach”. Students, unintentionally imitating her gesture, built a new community while building a new gesture for themselves. I do not wish to go too far, but I cannot help to wonder whether in that moment a community of friendship and research come to light (Lewis and Jasinski, 2021)

However, what is enough clear is that in both Giovanna’s and Davide’s case, through online teaching emerged an environment of intimacy, which deeply transformed students’ receptivity to both teacher’s words and the emerging community. Students became more sensitive, susceptible to transformations, open to what is being said. Davide’s sense of joy and discovery while giving lesson enables us to see how teaching is an ongoing pointing to that region in which education and community joyfully emerge, while Giovanna’s experience speaks about a sense of collective, ongoing delving into the topics being discussed. Their words bear witness to an educational experience in its own right, one in which a realm of joy, freedom, fulfilment and learning may emerge. “The fact of natality… the miracle that saves the world” (Arendt, 1998/1958, 246) is displayed in Davide’s and Giovanna’s witnesses. In this sense, education illuminates the territory between what is known and the open space of radical possibilities before us. It is exactly such an unpredictable space of pure, radical possibility that is worth exploring educationally.

References

Arendt, H. (1977/1961). “What is Freedom?” in Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. Harmondsworth, Penguin Books.

Arendt, H. (1998/1958). The Human Condition. Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press.

Birmingham, P. (2006). Hannah Arendt and Human Rights: The Predicament of Common Responsibility. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

d’Agnese, V. (2016) Facing paradox everyday: a Heideggerian approach to the ethics of teaching. Ethics and Education, 11(2): 159-174.

Feinberg, W. (2006). For Goodness Sake: Religious Schools and Education for Democratic Citizenry. New York, Routledge.

Hansen, D. (2017). Among School Teachers. Bearing Witness as an Orientation in Educational Inquiry. Educational Theory, 67(1): 9-30

Heidegger, M. (1992/1928). The Metaphysical Foundations of Logic. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1992/1929-1930) The Foundamental Concepts of Metaphysics. World, Finitude, Solitude. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1996/1927). Being and Time. Albany, State University of New York Press.

Heidegger, M., (1982/1927), The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Levinson, N. (2001). “The paradox of natality: Teaching in the midst of belatedness,” in Hannah Arendt and Education: Renewing Our Common World (Ed. Gordon, M.). London, Westview Press: 11-36.

Lewis, T. E.; Jasinski, I. (2021). Rethinking Philosophy for Children. Agamben and Education as Pure Means. London, Bloomsbury.

Mejia, A. (2008). My Self-as-Philosopher and My Self-as-Scientist Meet to Do Research in the Classroom: Some Davidsonian Notes on the Philosophy of Educational Research. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27(2–3): 161–171.

Santoro, D.A. (2015). Philosophizing About Teacher Dissatisfaction: A Multidisciplinary Hermeneutic Approach. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 35: 171-180

Shuffelton, A. (2015). Estranged Familiars: A Deweyan Approach to Philosophy and Qualitative Research. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 34: 137-147.

Thomson, I. (2013). Death and Demise in Being and Time, in Heidegger’s Being and Time (Ed. Wrathall, M.) Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 260-290.

[1] By prior agreements, the interviews are anonymised; teachers’ names are pseudonyms.

[2] Witness gathered during the course’s conversations.

[3] Witness gathered through in-depth interview.

[4] Witness gathered during the course’s conversations.

[5] Witness gathered through course’s conversations and in-depth interview.

[6] Witness gathered through in-depth interview.

Abstract

This paper explores Bertolt Brecht’s view of the relationship between education and the theatre, with particular reference to his notion of the Verfemdungseffekt and gestus. Epic theatre aims to educate its audience into a form of critical, practical curiosity about the world. Positioning his theatre as being anti-Aristotelian, Brecht seeks to not only make social reality recognisable in the theatre. He wishes to render possible (through the V-effekt aesthetic) the observation of the social and aesthetic processes, which bring forth what we name our reality. I will show that Brecht’s pedagogical intention pivots around his (rather Aristotelian) view that pleasure resides at the heart of the theatrical mimetic task. This is a pleasure that does not however emerge from Aristotelian identification, but instead from theatre’s pedagogical task. Brechtian theatre wishes to make observable the coming-into-meaning of our ideas about, and representations of, the world. As a form of concept-making, theatre is hereby called to not erase individual experience in the name of representing higher ideals. Theatre is tasked instead to not obscure the uneasy congruence between the individual’s experience of the world and its ideal presentation (in the metaphors of art, science). The artist is to acknowledge this theory-practice connection in the imitations of the world that s/he creates, as well as in her/his conduct towards the audience. Theatre is not to aim to ‘govern’ the audience through its images by instructing them into a worldview. It is to position people’s innate capacity to reason and govern themselves at the heart of theatrical mimesis. The V-effekt acts hereby as an aesthetic pedagogy that is to forestall Aristotelian catharsis, and with that, the act of instruction into a fixed image of the world. The ‘dialectic (non-Aristotelian) theatre’ is to instead heighten the contradictions of a mimetic work that creates as much as it represents things, people and actions. As a consequence, the theatre leaves a productive, pedagogic gap that can only be ‘closed’ by the audience’s own consideration as to the truth of what is presented to them on stage. In other words, the pedagogical act is not to be fully controlled by the artist. Brecht’s somewhat anarchist educational tendency is hereby revealed in his concern with the artist’s role in creating the conditions for social virtues and human propensities to flourish. Attending to the productive conditions specific to the theatre, the artist is to care for its ultimately ‘superfluous’ creation of metaphors about human actions. Drawing on Brecht’s Me-ti texts (and editor Antony Tatlow’s editorial comments), I will also show how Brecht’s concern with the interdependent relationship between theory and practice echoes his own examination of the Marxist-Leninist doctrinal distinction between idealism and materialism. This includes its materialism’s assumption that the individual’s consciousness simple reflects matter (as ‘real being’), but cannot shape (or question) it. As a last step in the paper, I will look at actress Helene Weigel’s gestic acting in her role as Mother Courage. Her gestus of showing the complex process of Courage’s (self-)formation, productively illustrates Brecht’s pedagogical concern. The modern theatre is to not obscure, but make observable in mimesis, the ‘critical dialectical’ relationship between an individual’s conscious experience, their actions in the world, and the material circumstances they live in.

Brecht in Philosophy of Education Journals

Bertolt Brecht is certainly no total stranger to Philosophy of Education Journals in the Anglophone world. His work, however, is normally only touched upon relatively briefly, and placed as part of broader discussions around the nature and purpose of the arts (film, media literacy, socially engaged public arts) in/as education (Yun 2021; D’Olimpio 2014; Kellner 2021). More sustained engagement with Brecht’s work is rare. An exception presents Alan Scott (2013), who explores the role of Brecht’s estranged, realist theatre as a form of political education. (Applied) theatre-focused publications in turn engage with Brechtian theory and practice usually in relation to specific educational institutions and educational theory. Just to mention a few: Franks and Jones (1999) re-read Brecht’s theatre theory for its contribution to the pedagogic underpinnings of drama and media education. Russo (2003) applies Brecht to educational theory (esp. Vygotsky’s ‘zone of proximal development’), drawing a comparison between progressive education’s student-centred and Brecht’s audience-centred pedagogy. Otty (1995) connects Brecht’s Lehrstücktheorie to Freire’s conscientization and Boal’s theatre; and my own publications have looked at Brechtian theatre pedagogy as a ‘philosophical ethnography’, that prioritises a productive over a representational orientation in education research (Frimberger 2016; 2017). Rather than ‘applying’ Brecht to a particular educational context, institution, or putting his work in service of progressive theory, this paper is driven by a curiosity to explore Brecht as a philosopher of education on his own terms. But I first need to manage the readership’s expectations. ‘Brecht was not a systematic thinker tied to one specific mode of [textual] reflection, but rather he developed and tested his ideas across various literary and non-literary genres. As a result, many of his key insights are reiterated in multiple forms, for example: as dramatic dialogue, song text, journal entry, aphorism, prose fragment, and theoretical essay (…)’ (Wessendorf, 2016, p. 122). In other words, we will encounter Brecht the philosopher of education and his theatricum philosophicum (ibid), not in the systemacity of his ideas (alone), but only when reading his reciprocative theatricalisations of ideas in the same productive, interpretive stance, which he demanded of his audiences. Let us start the journey then with Brecht’s arguably most well-known piece of theory in the Anglophone world.

Theatre as Knowledge

Brecht’s Short Organum for the Theatre (written in 1947/8) was produced at the tail end of his exile years, just before he settled in (post-WWII) East Berlin. The unusual title Organum (meaning ‘a body of principles’), written in 78 aphorisms - short pithy statements in prose – refers, in form and title, to renaissance scientist Francis Bacon’s 1620 book Novum Organum (2019). Brecht was likely attracted to making the link with Bacon and his empiricist natural philosophy, as a way of giving aesthetic expression to his own (implied) anti-Aristotelian ‘scientific’ position in the theatre (Brecht 1978, p. 205). Bacon’s interpretation naturae is considered the ground work for what we now think of as the scientific method. With its emphasis on empirical and rational observation, and methodical, inductive reasoning, it was composed as an ideological refutation of Aristotelian deductive logic as anticipation naturae in his Organon (2017). Brecht indeed shared Bacon’s concern regarding the authoritative finality of concept-making that can potentially result from a purely anticipatory approach, even when supposedly grounded in the scientific observation of the material world. This is reflected in Brecht’s own critical examination (from the 30’s) of the Marxist-Leninist doctrinal distinction between idealism and materialism; and its (practical, political-tactical) assumption (turned into dictatorship under Stalin), that consciousness is solely determined by matter as ‘real being’(Brecht, 2016, p.18). In Nietzschean (1873) fashion, Brecht reminds his fellow countrymen in particular of the danger of obscuring that theory and practice are interdependent. Knowledge, Nietzsche and Brecht would agree, might be best considered (playful) metaphor rather than eternal truth. And knowledge is to firstly serve life, rather than a narrow conception of (e.g. rational) truth. It is to aid our understanding as to how our human cultural productions - including our political systems and our concept-making - nourish (or stifle) our human capacity to live a flourishing life. Accordingly, Brecht warns his fellow artists to not forget (and deny in their artistic expressions) the pleasure of playful exploration that resides at the heart of our acts of knowledge production.

‘And here one again let us recall that their [the artists’] task is to entertain the children of the scientific age, and to do so with sensuousness and humour. This is something we Germans cannot tell ourselves too often, for with us everything slips into the unsubstantial an unapproachable, and we begin to talk of Weltanschauung [worldview/ideology] when the world in question has already dissolved. Even materialism is little more than an idea with us. Sexual pleasure with us turns into marital obligations, the pleasures of art subserve general culture, and by learning we mean not an enjoyable process of finding out, but the forcible shoving of our nose into something (…)’ (Brecht 1978, p. 204)

Education in the theatre is to be a joyful process of finding out about the world. It is not meant to be an act of moralising from the stage. It is no self-satisfied act of shoving one’s nose into how people live up to, fail, or can be best instructed into a set of universal norms. This applies even if these norms are evoked in the name of greater idea(l)s (‘culture’, ‘materialism’, ‘marital obligations’). Theatre, Brecht claims, would in fact ‘be debased’ if it tried to become a ‘purveyor of morality’ and failed to make its ‘moral lessons’ enjoyable - not only to people’s reason, but also to their senses (ibid, p. 180). In an earlier essay (written in the 1930’s), Brecht already highlights the inadequacy of art when it only anticipates the nature and workings of ‘the great and complicated things that go on the world’ (ibid, p. 73). Theatre is instead to draw on the insights and methods of the new sciences of his time (e.g. modern psychology).

‘People are used to seeing poets as unique and slightly unnatural beings who reveal with a truly godlike assurance things that other people can only recognise after much sweat and toil. It is naturally distasteful to have to admit that one does not belong to this select band. All the same it must be admitted’ (…) (ibid, p.73).

This is of course not to imply that, in Brecht’s view, art is science or that art should operate by the same means. Even if the artist makes use of the (new) sciences, in order to gain an understanding of an increasingly complicated modern world. The poet’s task is that of translating any such knowledge about the world into poetry. ‘Whatever knowledge is embodied in a piece of writing has to be wholly transmuted into poetry. Its utilization fulfils the very pleasure that the poetic element provokes (…)’(ibid, p. 74). In other words, the pleasure evoked by poetry is to be derived from aesthetic elements that are indeed shaped by the poet’s efforts to ‘penetrate deeper into things’. Most importantly however, this search for ‘truth’ is always to be undertaken with a view to the artist’s primary task: to entertain his audiences ‘with sensuousness and humour’ (ibid). Given Brecht’s eudemonistic emphasis, he echoes a rather Aristotelian premise. Theatrical mimesis allows artists and audiences to exercise their capacity for recognition and understanding; an activity, which is naturally pleasurable to humans (Poetics, 48b12-17).

Brecht’s anti-Aristotelianism

As part of his (self-styled) anti-Aristotelianism however, Brecht critiques a way of making modern art that represents an unchangeable world. He critiques a presentation of world that is either determined by invisible metaphysical forces or by individual motive forces alone - especially when these are represented as the result of (an already) fully formed moral character in-action (Brecht, 1987, p. 70). Brecht rejects certain poet’s overreliance on individual feeling and individual artistic intuition, when it is devoid of the commitment to investigate the complicated workings of those cultural productions that mark the (modern) world. These modern phenomena include the individual politician’s ‘lust to power’, embedded in the very workings of politics; as much as the coming into being of a (Nazi) propaganda newspaper (like the Völkische Beobachter); the workings of global capitalist business (his example is Standard Oil); as well as the complicated moral discourse around war-profiteering (ibid, p. 73). But Brecht’s antagonism towards Aristotle must also be considered as part of Brecht’s dialectical theatricalisation of ideas. Aristotle was by no means simply an ‘ideological opponent’ for him. Brecht in fact accords with Aristotle’s emphasis on theatre’s mimetic function. ‘Tragedy [drama] is not an imitation of persons, but of actions and of life’ (Poetics, 50a16f). Flourishing, for both Brecht and Aristotle, can only be achieved in action. And the imitation of such actions, as to how one flourishes (or perishes) in life and death, are the stuff of (both their) theatrical mimesis. As already hinted at, Brecht also affirms Aristotle’s eudemonistic premise. ‘Thus what the ancients, following Aristotle, demanded of tragedy is nothing higher or lower than that it should entertain people (...)’ (ibid, 1978, p.181). Brecht however refuses Aristotle’s position on the nature of this theatrical pleasure. And he differs with him also with regards to the kind of aesthetics that is to constitute a ‘plausible’ theatrical imitation of life’s actions. According to Aristotle, the well-constructed tragedy is to bring forth a pleasurable experience in the audience. It is to evoke empathy with the fate of the hero and the arousal of the tragic emotions of fear and pity, and their subsequent physical relief as catharsis (Poetics, 53b10f; 49b27f).

‘This [Brecht’s] dramaturgy does not make use of the ‘identification’ of the spectator with the play, as does the aristotelian, and has a different point of view also towards other psychological effects a play may have on an audience, as, for example, towards the ‘catharis’. Catharsis is not the main object of this [Brecht’s] dramaturgy. It does not make the hero the victim of an inevitable fate, nor does it wish to make the spectator the victim, so to speak, of a hypnotic experience in the theatre’ (Brecht, 1978, p. 78).

The pleasure of recognition, according to Brecht, does not reside in a theatrical mimesis that stimulates tragic emotions and their cathartic release, because it shows the world as it is. The pleasure of the poetic element, for Brecht, emerges from theatre’s pedagogical function. Theatre is tasked with not only making reality recognisable in the theatre (‘as does the aristotelian’), but with opening out for consideration to an audience the very aesthetic-social processes that constitute this imitated ‘reality’ in the first place. Through a theatrical mimesis that is to appeal to people’s reason and their senses pleasurably, Brecht aims to educate his audience into a disposition of a certain practical (critical) curiosity. The (aesthetic) gesture of showing/pointing to theatre’s double mimetic activity is hereby at the heart of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt. The (Aristotelian) theatre of illusion emphasises the spontaneous unfolding of actions in front of the audience, as if these happen for the first time. Brechtian Verfemdungs- theatre deliberately points to the fact that its theatrical activities are imitations of actions that have already taken place. It doesn’t hide the rehearsed nature of its performances or the fact that texts have been learned by heart. In fact, it aesthetically heightens theatre’s artifice. It brings forth the contradictory nature of its imitative work by revealing – and putting in juxtaposition (in acting, stage design, lighting, music) - its various processes of production. The Verfremdungseffekt does hereby not just serve an aesthetic but a social-dialectical function. It is to make striking and strange (to audience and actors alike) what is normally taken for granted about people and their actions in the world. In other words, it is to instigate a practical philosophical inquiry into human being (as a noun and verb). Theatre is to turn spectators (as well as actors, as we will see later) into observers and commentators on the very reality that is brought forth on stage. Asserting the pleasure that resides at the heart of theatre’s acts of knowledge production, the audience is invited to deliberate. How do social phenomema (like war, politics, business) and the concepts and discourses that give life to them map onto people’s everyday life actions, and their capacity to live a flourishing life therein? This philosophising audience is hereby conceived as ‘a collection of individuals, capable of thinking and of reasoning, of making judgements even in the theatre; it [epic theatre] treats it as individuals of mental and emotional maturity, and believes it wishes to be so regarded’ (p. 79).

(In)complete images of the world

Through the V-effekt, Brecht seeks to draw attention to the (often) uneasy congruence between our everyday, material experiences and their ideal representation. The dialectical theatre is to evoke reflection. How is it that explanations of the world can end up governing the very world and people that they seek to represent? As Brecht’s Daoist-inspired teacher Me-ti (2016) formulates it:

‘Judgements reached on the basis of experiences are not usually connected as are the events that led to the experiences. The combination of judgements does not amount to an exact image of the events that gave rise to them. If too many judgements are connected with each other, it’s often very difficult to reconstruct the events. It takes the whole world to come up with an image but the image does not include the whole world. It is better to connect judgements with experiences than with other judgements, if the point of the judgements is to control things. Me-ti was against constructing too complete images of the world’ (p. 50).

As editor Tatlow suggests, the Me-ti texts also echo Brecht’s own engagement with what happened to Marxism. Me-ti can be read (in parts) as a (poetic) reflection on ‘dialectical determinism’ (e.g. under Stalin; later the GDR) and its disregard of people’s ‘experience’ of socialism; including the control and censorship of individual ‘dissident’ productions (ideas, art) in the name of freedom from bourgeois rule (ibid, p. 21). Brechtian theatre’s key artistic-pedagogical premise then pivots around the (anti-Aristotelian) artistic distanciation (Verfremdung) of the audience’s full identification with the images of the world, presented in the world – and of course on stage. Aiming to forestall catharsis, Brechtian mimetic practice is to bring forth a stance of active observation and inquiry: into the productive relationships that constitute the coming-into-meaning of our images of the world. In order to serve such pedagogical aim, theatrical representation, as a form of concept-making that positions art as a form of knowledge, has to be also wary of its own anticipation naturae. In other words, the ‘scientific theatre’ must not sever and obscure the connection between theory and practice in its own imitations, so as not to ‘debase’ the theatre into a ‘purveyor of morality’ (Brecht, 1978, p. 180). Brecht seems indeed aware of the tricky balancing act required of the (modern) theatre. On the one hand, he does not wish to obscure that his theatre indeed pursues a pedagogical intention to influence the way that people attend to/intervene in the social world. And having a pedagogical intention of course implies that the theatre has a view-point. It has ‘moral lessons’ to convey, even if these are partial and not a closed Weltanschauung. On the other hand, Brecht is conscious of the danger. A pedagogical intention, when too willingly burdened by a theatre claiming a ‘higher status’, can too easily obscure that it is in the business of metaphor-creation. And as such, it can slide into normative impositions as to how people should think and act. Brecht was indeed accused of betraying his own ‘scientific’ principles, even by his admirers, such as the philosopher Paul Feyerabend (1991). Feyerabend lauded Brecht’s anti-ideological, dialectical approach to presenting knowledge in poetry (e.g. in his 1939 poem To those who follow in our wake). Feyerabend praised his poetry for the way it 'enlarges faults and lets different incommensurable jargons run side by side' (Feyerabend, 1991, p. 95) without harmonising different aspects into a more systematic account. But he also accused Brecht (many of his plays in particular) of humourless, Marxist intellectualism and, indeed, of moralising from the stage (ibid: p. 81; 143). Brecht then perhaps reminds himself, e.g. in is Organum. Epic theatre is not only tasked with making enjoyable the very act of inquiry into the workings of the social world. It is also called to acknowledge, through the kind of imitations it presents, that its audience is capable of reasoning and governing themselves. ‘There is such a thing as leaving mankind alone; there is no such thing as governing mankind’, as Oscar Wilde (2018, p. 15) formulates his view on the role of socialism for the attainment of individualism. Wilde points us to Daoist philosopher Chuang-Tzu. In the fictional persona of the Chinese elder in his Me-ti, Brecht equally evokes the Daoists’ dislike for (Confucian) moral teachings, critiquing the espousal of virtues as a way of organising and controlling populations.

‘There a few occupations, which so damage a person’s morals than the occupation with morality. I hear it said: You must love the truth, you must keep your promises, you must fight for the good. But the trees don’t say: You must be green, you must let the fruit fall vertically to the ground, you must rustle the leaves when the wind passes through them’ (Brecht, 2016 p. 70).

Too much normative imposition - ‘too much administration, whether moral or political is counterproductive’ to human flourishing, Tatlow (ibid) comments in his editorial notes. Me-ti’s reflections on the nature of morality echo Brecht’s own struggle with his theatre’s striving for a ‘higher status’ and the (perhaps) ever looming desire of becoming a ‘purveyor of morality’ to the masses. The temptation of the abstractions of Western thought (e.g. mirrored in Brecht’s own Marxism) is here counteracted with Daoist-inspired allegorical description. Nature’s drive to life needs no further justification in abstraction; other than a pointing to what nature does. The human capacity for life, Me-ti implies, is not spawned through normative imposition. It is fostered instead by creating the productive conditions for growth, so people can act freely on their innate capacities. This is however not a simple act of ‘leaving mankind alone’. Brecht clearly pursued a pedagogical intention to influence ‘mankind’s’ relation to social reality. He presumed that a better society has to be actively created, even if our human capacity for living a flourishing life is innate. As is evident, Brecht wished to radically challenge the institutions (artistic, political, economic) of his time, driven of course by his first-hand experience of fascism. Theatre was considered to play a part in creating the conditions for a socialist future. But as to what kind of social-ism was exactly to be endorsed on a political level was a recurring question over his life-time.

As Brecht’s exchanges with ‘dissident’ Marxist philosopher and life-long teacher Karl Korsch (2012), and his Me-ti texts (which were likely inspired by their discussions), reveal, Brecht struggled with Marxist-Leninist’s false idealist/materialist distinction. Dialectical determinism turned materialism into a ‘doctrine equated with Being, which consciousness simply reflects, but does not shape or question’ (Tatlow/Brecht, 2016, p. 25). And Brecht experienced of course the disastrous results of its politics. Many of his collaborators (e.g. the actress Carola Neher and director Asja Lācis), communists who had moved to the Soviet Union after the revolution were, under Stalin, branded Trozkyist spies and part of a literary opposition. Seen to undermine the higher purpose of (Soviet realist) art for the direct illustration of Marx's class laws (Paškevica, 2006, p.118f), they were imprisoned and forced into labour camps (Gulags). As Reinhold Grimm (1979) aptly summarises Brecht’s (necessarily tragic) political position:

‘The Marxist Brecht was faced with a terrible decision. In service of the final humanising of human beings, in which he believed, he either had to demand their total de-humanisation and objectification … or to question – even to negate - this ideology, his life’s and work’s prime value.’ (p. 100)

It might be argued then that Brecht reveals, in his pedagogical and aesthetic ideas, what we shall call a certain social- anarchist tendency (likely inspired by Korsch, 2012). In other words, he can be said to share anarchism’s pedagogical ‘faith in the idea that human beings already possess most of the attributes and virtues necessary to create and sustain such a different society, so do not need to either undergo any radical transformation or to do away with an ‘inauthentic consciousness’ (Suissa, 2010, p. 149). In fact, in Me-ti, Brecht comments on Marx’s observation that consciousness is shaped by being or ‘life’. e.g. the way we make a living. For him, this interdependency does not prove people’s in-capacity for reason or joy in life. Brecht simply points to the undeniable dependency between our ideas about the world and how we engage with it materially. He admits that Marx’s observation sounds rather depressing, but suggests pragmatically that ‘the simple realisation that all great works were nevertheless created in this dependency and that conceding this dependency doesn’t make them any less great, settles the matter’ (Brecht, 2016, 76). Brecht also argues that Marx’s principle of the dependency of thought won’t seem so depressing, when dependency on the economy won’t be felt as so oppressive anymore by people. Brecht’s unorthodox Marxist, perhaps anarchist, proclivity then takes shape in his pedagogical positions. He believes in the capacity to reason of his theatre-going audience. He emphasises theatre’s eudemonistic role. Brecht refuses to (fully) instrumentalise theatre for an abstract, ‘higher’ cause, disconnected from people’s individual experience. And he believes that too much (moral, political, social) governance stifles people’s capacity to be good, and live a flourishing life. A certain anti-teleological notion is equally articulated in his belief that the artist cannot control the pedagogical/political outcome of his artistic work. In other words, the exact pedagogical outcome between what is presented to an audience in the materiality of theatre, and the way that the audience interprets and acts (or not) on the insights thus gained, must remain unpredictable.

‘Not even instruction can be demanded of it [the theatre]: at any rate, no more utilitarian lesson than how to move pleasurably, whether in the physical [aesthetic] or the spiritual [moral] sphere. The theatre must remain something entirely superfluous, though this indeed means that it is the superfluous for which we live. Nothing needs less justification than pleasure’. (Brecht, 1978, 180-181)

The conditions for change can be created, and the effects of this (indirect) education can be of course ‘hoped for’. But it is firstly in the careful attending to the productive conditions particular to the theatre – e.g. when (co)-creating the aesthetic imitations of theatre’s ultimately ‘superfluous’ and necessarily playful metaphors - that the artist can hope to influence his audiences. In other words, Brecht draws attention to what it means for an artist to partake in the (indirect) creation of conditions (e.g. in the theatre) for the purpose of ‘social virtues and human propensities to flourish’ (Suissa, ibid) – in a way that does not deny the relation between theory and practice. Tatlow (Brecht, 2016) reminds us (p. 53) hereby of the very purpose of the Verfremdungseffekt. It is to not only invite inquiry into the productive relationship between theory and practice in ‘other’ acts of cultural production. The V-effekt is to render possible the questioning of Brechtian theatre’s own artistic and pedagogical ways and means of presenting the world on stage. The audience is to be invited to read and judge: do theatre’s metaphors still ‘move pleasurably’ and ‘superflously’? - or have they hardened into a Weltanschauung? Are the images disconnected from the particularity of their emergence in (everyday life) practice, and the question of people’s flourishing therein? Do they seek to organise and govern the world in their own image? Do they create the conditions for social virtues to flourish? If Brecht himself honoured, or failed, his own principles has of course been discussed (see e.g. Arendt, 1948; Feyerabend 1975; Bloch et al. 1977). What can perhaps be stated for the purpose of this paper, is Brecht’s intention. Tatlow gets to its heart in his editorial footnote to Me-ti: ‘Brecht disliked any (artistic) practice without space to question its aesthetic intentions. In such a world you either manipulate or are manipulated. To provoke such questions was, of course the purpose of the so-called estrangement effect (Brecht/Tatlow, 2016, p. 53).

Gestus in Mother Courage

Having established the pedagogical role of Brecht’s ‘anti-Aristotelian’ aesthetics, I now wish to illustrate its coming-into-meaning in the acting practice of one of his closest collaborators: the actress (and his wife) Helene Weigel. In accordance with Brecht’s key idea, that the ‘producer of ideas’ should not obscure the reciprocative translations between theory and practice, I will focus on a practice example from Weigel’s portrayal of Mother Courage (in the eponymous play). Brecht wrote the play in Swedish exile in 1939, in just over a month, as a furious reaction to Hitler’s occupation of Warsaw, Poland. Due to the looming Scandinavian occupation, the play was premiered, in Brecht’s absence, in neutral Switzerland (Zürich) in 1941 (Brecht, 2015, p.181). Unable to assert his directorial influence, Brecht was disappointed that his play seemed to have evoked an unwanted Aristotelian catharsis in the audience. They had read Mother Courage (as Brecht wrote in his journal) as a ‘hymn to the inexhaustible vitality of the mother creature’ (ibid); a mother who victoriously thrives in the face of an inescapable fate (‘war’). When returning to Europe in 1947/48, he immediately revised the script to make Courage a less sympathetic character. She was not be so easily assimilated as an unchanging mother archetype. Her social behaviour and attitude were to provoke more uneasy questions as to the processes of her (self)formation. The result of the script changes led to the 1949 production in East Berlin at the Deutsches Theater, whose success firmly placed epic theatre on the (East) German arts scene’s map. Like all of Brecht’s plays, Mother Courage is historicized, in order to shine a new light on contemporary issues. It tells a story from the past. Mother Courage is set in 17th century Europe during the Thirty Year War; one of the most destructive wars in European history, fought over struggles for political hegemony and religious allegiances. The play explores the complicated (dialectical) process of moral (self)formation set in motion by our concrete ways of engaging with each other and the physical world around us. It deals with the complexity of formative processes in situations when finding ourselves in de-humanizing social structures that are not of our own making. In other words, it explores what (moral) formation means in those conditions that are not conducive to the flourishing of social virtues and human propensities. The play follows the fortunes of Anna Fierling known as Mother Courage. A feisty canteen woman with a keen sense for business, she is determined to feed herself and her children, and make a good living, by selling provisions to soldiers on the battlefields of Europe. We first encounter Courage pulling her cart loudly and proudly and ready for business. Over the course of the play and her various business dealings, we see her lose all her three children - Schweizerkass, Eilif and Kattrin - to the very war that she hoped to make a profit from. And surprisingly, at the end of play, even after her money has run out, her children have all been killed, and peace has arrived, she still pulls her cart towards what she hopes will be the next (profitable) battlefield. ‘A play is therefore more constructive than reality, because in a play the situation of war is set up as an experimental situation, for the purpose of giving insight; that is the spectator assumes the attitude of a student – provided the type of performance is right’ (Brecht, 2015, p. 221). When watching a play as an experimental educational situation, the audience is to have enough distance from the events and characters on stage. They are to compare, and criticise, the various influences that form human behaviour, as well as to consider the implied alternatives. The art of incorporating the V-effect into the art of acting was hereby a key way of making this observation of the character’s (self-)formation possible.

‘When s/he [the actor/actress] appears on stage, besides what s/he is actually doing, s/he will at all essential points discover, specify, imply what s/he is not doing; that is to say, s/he will act in such a way that the alternative emerges as clearly as possible, that this acting allows the other possibilities to be inferred and only represents one out of the possible variants (…) whatever s/he doesn’t do must be contained and conserved in what he does. In this way, every sentence and every gesture signifies a decision; the character remains under observation and is tested. The technical term for this procedure is ‘fixing the “not ... but”.’ (Brecht, 1978, p. 137).

Gestus describes the various ways that the actor makes manifest these ‘not…but’ moments in the art of acting. She is to show the complicated and contradictory social influences and personal decisions that have lead to the character’s (self)formation. Gestus is brought to presentation through gestures, postures, tone of voice, facial expression, ways of handling props, and standing in relation to other characters on stage. As such, it is an expression of a ‘social attitude’ rather than of the character’s fixed psychological make-up. ‘Human behaviour is shown as alterable; man himself dependent on certain political and economic factors and at the same time as capable of altering them’ (ibid, p. 86). Not all of the actor’s gestures embody gestus of course. It is only those gestures which act as social gests; ‘the social gest is the gest relevant to society; the gest that allows conclusions to be drawn about the social circumstances’ (ibid, p. 105). Brecht explains:

‘(…) one’s efforts to keep one’s balance on a slippery surface results in a social gest as soon as falling down would mean ‘losing face’; in other words losing one’ s market value. The gest of working is definitely a social gest, because all human activity directed towards the mastery of nature is a social undertaking, an undertaking between men. On the other hand, a gest of pain, as long as it is kept so abstract and generalised that it does not rise above a purely animal category, is not yet a social one…The “look of a hunted animal” can become a social gest if it is shown that particular manoeuvres by men degrade the individual man to the level of a beast (…)’ (ibid, p. 104-105).

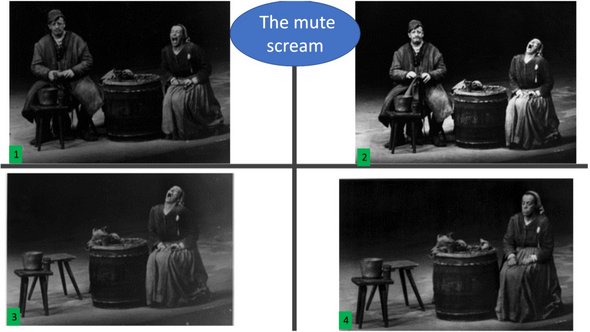

Helene Weigel’s gestic acting is documented in Ruth Berlau’s extensive 1949 production photographs for the Courage Modellbuch (Brecht, 2015). They illustrate how gestic acting productively translated, and with that also co-created, Brecht’s pedagogical intention. Gestus renders observable the non-teleological - what Tatlow (Brecht, 2016, p. 29) calls ‘critical dialectical’ - relationship between an individual’s conscious experience and the material social world they find themselves in. There are many of Weigel’s fine acting moments documented in the modelbook. Given the limitations of the paper, I will focus on the ‘mute scream’ sequence in scene three. It is here where we learn that Courage's honest son Swiss Cheese has been arrested and is about to be executed by the enemy army (the Catholics). He did not hand to them the regiments' cash box of the besieged army (the Protestants), which he was entrusted with as their paymaster. The honest Swiss Cheese, when realizing that the enemy was trailing him, threw the cashbox in the river. Captured by the army, he is now suspected of keeping it hidden somewhere. He is threatened with execution. The camp prostitute Yvette, a sympathetic friend of Mother Courage, wants to help her to get her son back. She uses her intelligence and wit to convince the officer (called ‘One Eye’) responsible to court martial Swiss Cheese to let him free - for the price of 200 florins. Yvette also arranges for an admirer to buy her Courage’s cart as a gift, so the ransom can be paid. Courage agrees to the asking price of 200 florins and sells Yvette her beloved cart. Courage is aware of the urgency of the situation. But she also realises that she and her daughter Kattrin will run the risk of becoming destitute, when losing their way of making a living. Secretly, she had hoped that her son had hidden the cash box somewhere. She had hoped that she would be able to use that money to buy back her cart later. But when she learns that honest Swiss Cheese was in fact (again) too honest, and threw the cashbox in the river, she makes the decision to haggle over the demanded ransom. Finally, she offers 120 florins instead of 200 for his release. At the key turning point in scene three, Yvette has raced three times to haggle with the officer holding Swiss Cheese captive. Yvette is furious at Courage’s stubborn refusal to pay the full asking price, regarding it as a straightforward betrayal of her son.

‘YVETTE comes running in.

Yvette: They won't do it. I warned you. One Eye was

going to drop it then and there. There's no point, he

said. He said the drums would roll any second now

and that's the sign a verdict has been reached. I

offered a hundred and fifty, he didn't even shrug.

I could hardly get him to stay there while I came

here.

MOTHER COURAGE: Tell him I’ll pay two hundred. Run!

YVETTE runs. MOTHER COURAGE sits, silent.

The CHAPLAIN has stopped doing the glasses

I believe—I've haggled too long.

In the distance, a roll of drums. The chaplain stands

up and walks toward the rear, mother courage re-

mains seated. It grows dark. It gets light again,

MOTHER COURAGE has not moved. YWETTE appears, pale’ (Brecht, 1966, p. 63-64).

Yvette runs off once more to see if she can save Courage's son by offering the full price. Meanwhile, we see Courage and the Chaplain sit in silence, motionless. In the distance we hear drumming - the sign that Courage' son is now being executed. And here, the mute scream sequence starts.

(Brecht, 2015, p. 211f.)

Two minutes of silent screaming by the actress. Her mouth is wide open, head raised, but no sound is heard. In the only bit of dialogue in this sequence, Courage admits her mistake: ‘I reckon I bargained too long’ (p. 64). The chaplain gets up silently and goes to the rear. Mother Courage remains seated. Her face is a screaming mask. She must have sat there for a long time, as the stage grows dark. The drumming stops. Then the stage grows light once more. Her son is dead. He has been executed. Yvette was too late. Mother Courage is still sitting in the exact position, when Yvette arrives. She tells her, full of righteous anger, that Courage got what she asked for. Courage already knows. Her hands are balled fists placed firmly on her lap. Courage is used to getting her way. In scene one, we witnessed her confident entrance. Her head was held high, loud singing voice, proud purveyor of provisions for soldiers. She knows how to get a good deal in a bad situation. She is used to traversing the theatres of war with cunning and humour - coming out the other side with a purse full of money. But here, we see, again, that all her learned behaviour; all the routines and talk and smart moves have their limits. They could not save her son. She did not calculate that she could not bargain with war. As the audience we are rightly exasperated with her. Does she not get it? Why does she still think she can win this one? Why does she still measure the value of her children's lives against the value of money? But things are complicated. Courage implored Yvette:

‘I need a minute to think it over, it's all so sudden. What can I do? I can’t pay two hundred. You should have haggled with them. I must hold on to something, or any passer-by can kick me in the ditch. Go and say I pay a hundred and twenty or the deal's off. Even then I lose the wagon.’ (ibid, p. 62).